As we find ourselves in between podcast episodes, in this interim newsletter we take a look at how Elvis’ professional fortunes were tracking in the summer of 1977 leading up to, and after, his untimely death on August 16th.

There has been a narrative develop, through press reviews of the time and subsequent biography, that the Elvis touring show was running out of steam by this time; that his audiences were deserting him due to some indifferent performances and poor press reviews and that, in desperation, he was consigned to playing smaller arenas outside of the major cities, sleepwalking through performances and no longer able to cut it in big city venues.

But the stats, and many favourable reviews from press and fans, tell a different story; for instance, he played the 20 000 seat Chicago Stadium four times within his final seven months on the road, and frequently played sequences of 10 000 - 18 000 seaters on road tours across the country. On June 26th, Elvis concluded what would prove to be his final tour with a sold-out performance to a big, enthusiastic audience of 18 000, at Market Square Arena, Indianapolis. The tour had encompassed ten shows, over consecutive nights, in ten cities over seven states, with total ticket sales of just under 117 000.

Contrary to what was claimed by Elvis’ father Vernon at the end of the television special, Elvis in Concert, filmed earlier in the June tour in Omaha, Nebraska and Rapid City, South Dakota, and which aired posthumously, the filmed performances were not from Elvis’ final show. In fact, he worked on for several days after the TV crews left the tour.

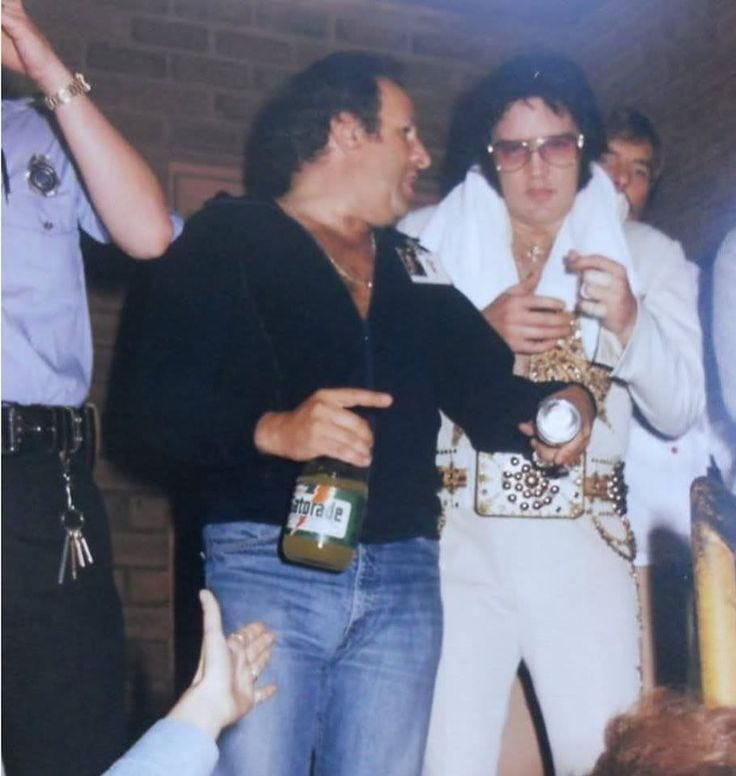

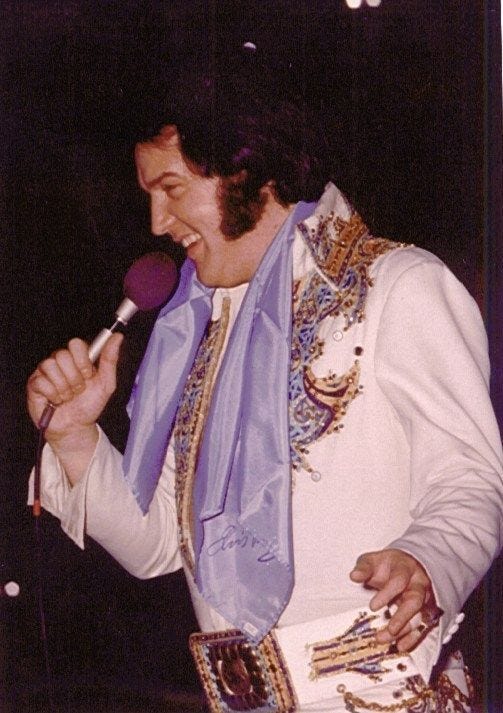

He wasn’t perfect, of course, and there were some off nights that left his band and management frustrated and the audiences puzzled and disappointed. But there were many nights, right up to the very end, when he was on fire, his voice sounded better than ever, and he could enthral a huge stadium audience right to the back row; without the support of Autotune, giant video screens, a stage full of dancers and elaborate lighting. He had fun with audience members, and with the band, was unfailingly polite to fans, and laughed at himself and his image. He no longer rehearsed, forgot lyrics occasionally (or couldn’t be bothered learning them in the first place), stopped and re-started songs if he wasn’t happy, and improvised on stage. He could be grumpy, especially with sound imperfections, and there were nights that he was homesick, lethargic, medicated and feeling unwell, all of which inevitably affected his performance. He struggled with his weight, addiction and mental health; had relationship frustrations, worries arising from ill-advised business ventures and his personal life having been laid bare in a tabloid book, yet he turned up, night after night, whether he felt like it or not. And there was no real alternative; revenues from record sales would not cover a fraction of Elvis’ monthly business and personal expenses, while the touring circuit, including the relentless sale of souvenirs and merchandise, remained hugely profitable even with the schedules more sedate than earlier in the 1970s .

The critics in local newspapers were not always kind, but also not always accurate. We’ve discussed this in a previous newsletter, taking a performance in St Paul, Minnesota, as an example of where reality and press accuracy dramatically diverged.

Elvis seemed to keep himself well insulated from the general reportage, although in Kansas City, Missouri, on June 18th, he did feel compelled to reassure the audience that, in spite of what they might have read or heard, he was happy, healthy, and enjoying his work.

The Indianapolis show that concluded Elvis’ final tour was widely seen as one of the better performances of his later career, and was reviewed in the Indianapolis Star by Rita Rose;

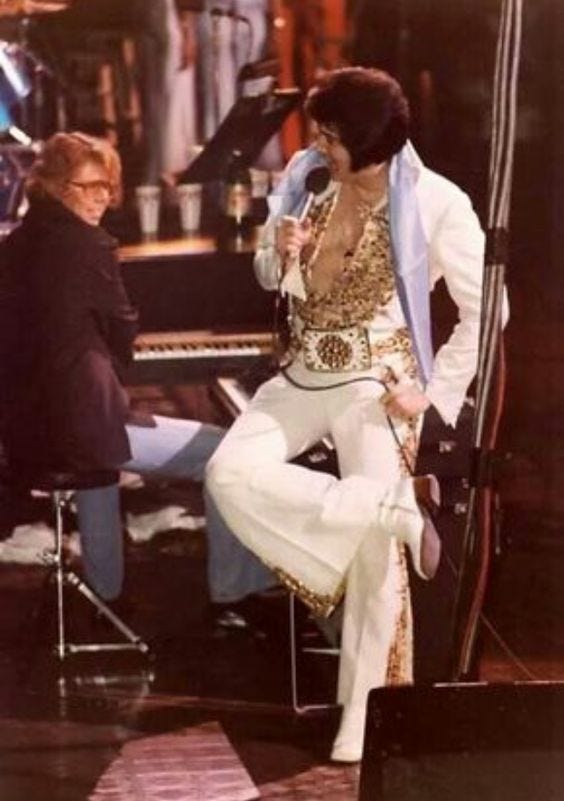

“…And then he appeared, in a gold and white jumpsuit and white boots, bounding onstage with energy that was a relief to everyone. At 42, Elvis is still carrying around some excess baggage on his mid-section, but it didn't stop him from giving a performance in true Presley style...”

It therefore begs the question; what if the cameras were in Indianapolis rather than Omaha and Rapid City? Elvis in Concert might have become one of the landmark entertainment specials of the 1970s, rather than an inconvenient truth that threatens Elvis’ twenty-first century cartoon-superhero marketability.

Elvis Presley Enterprises is currently (as of 2022) majority owned (85%) by a corporation, Authentic Brands Group, which controls marketing and promotion of Elvis’ image.

Elvis’ final two or three years on the road doesn’t quite represent their ‘superhero’ marketing strategy, so this period is largely ignored, and there remains no official release of the 1977 television special, Elvis in Concert. (Even though you can see it, and all the outtakes, on YouTube in various forms). It exists, and has been viewed by millions, whether they like it or not.

Late British-Australian writer Clive James recognised this dilemma early on, observing how much easier Elvis was to sell once his 'troubled physical presence’ was out of the way.

At the time of his death, Elvis was due to hit the road again, with a tour that would end with two nights in Memphis, at the 12 300 seat Mid-South Coliseum, the first time more than one hometown show for the year had been scheduled since 1974.

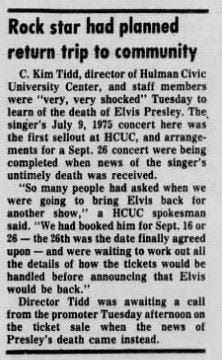

Elvis’ professional commitments extended well beyond the end of August. There was already a September tour being planned, with some dates confirmed.

(Information, tour stats and press cuttings are courtesy of Francesc Lopez at elvisconcerts.com)

Later in 1977, as part of his contract with the Las Vegas Hilton, Elvis was scheduled to open a newly renovated 5 000 seat showroom, the Hilton Pavilion.

This is the itinerary for his August tour:

Aug 17 - Cumberland County Civic Center, Portland, Maine

Aug 18 - Cumberland County Civic Center, Portland, Maine

Aug 19 - Utica Memorial Auditorium, Utica, NY

Aug 20 - Onondaga County War Memorial, Syracuse, NY

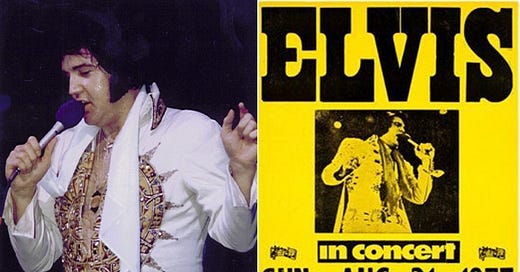

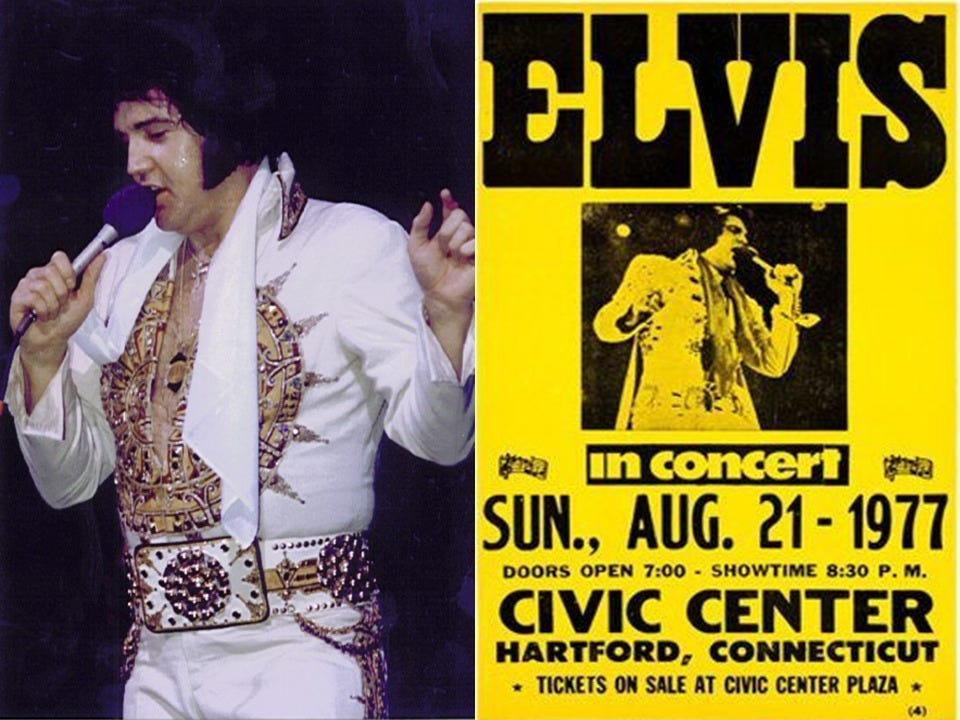

Aug 21 - Civic Center, Hartford, Connecticut

Aug 22 - Nassau Veterans Coliseum, Uniondale, NY

Aug 23 - University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky

Aug 24 - Roanoke Civic Center, Roanoke, Virginia

Aug 25 - Cumberland County Arena, Fayetteville, NC

Aug 26 - Asheville Civic Center Arena, Asheville, NC

Aug 27 - Mid-South Coliseum, Memphis, Tennessee

Aug 28 - Mid-South Coliseum, Memphis, Tennessee

These September dates were already confirmed at the time of Elvis’ death:

Sep 16 - Indiana State University, Hulman Civic Center, Terre Haute, Indiana (Initial date rescheduled for Sept 26)

Sep 21 - Huntington Civic Center, Huntington, West Virginia

Sep 22 - Huntington Civic Center, Huntington, West Virginia

Sep 26 - Indiana State University, Hulman Civic Center, Terre Haute, Indiana

Sep 28 - Savannah Civic Center, Savannah, Georgia

On August 16th, members of the touring band were enroute to Portland, Maine, by private aircraft. The plane had departed Los Angeles with scheduled pickups in Las Vegas and then Nashville, where clavinet player Bobby Ogdin and some other members of the touring party were waiting. Upon notification of Elvis' death, the flight was cancelled and the plane landed in Pueblo, Colorado.

According to Bobby Ogdin, interviewed by The Spa Guy, news of Elvis' death reached them in Nashville through the private airport's traffic controller, and following a phone call to Colonel Parker by producer Felton Jarvis, the 'Act of God' clause was invoked, meaning all their contracts were voided then and there. They were simply told, ‘everything is cancelled, go home’; their pay was stopped, and they were left to their own devices.

And then…

When Elvis passed away, there had been around 22 000 tickets sold for his two hometown shows at the Mid-South Coliseum, scheduled for the end of August.

There were initially only around 2 000 letters seeking refunds, and many ticket holders requested that the money be donated to Memphis charities, in honour of Elvis’ philanthropy. According to the Memphis Public Library, which holds many of the original refund letters, by 1982 nearly half of the $325 000 of ticket proceeds was still unclaimed. The Presley Estate, and the tour promoter Jerry Weintraub, issued legal proceedings to try and claim the outstanding amount for themselves, which had been held by Mid-South Coliseum management.

The ultimately pointless legal battle between the Presley Estate and Mid-South Coliseum (Presley V City of Memphis) took seven years, and in 1989, the court finally adjudicated that the money belonged to the ticket-holders, and no one else. The Coliseum was granted some reasonable administrative expenses, but was directed to forfeit the unclaimed ticket money (and interest) to the County, which would then attempt to repay the ticket-holders.

There is also an interesting story about a young Memphis lawyer named Blanchard Tual who was brought in to provide some independent scrutiny of the Presley Estate. Our regular podcast contributor Gary Wells has written about this here.

And in September 1978, Elvis’ booking at the Hilton Pavilion, Las Vegas, was fulfilled. Almost as if it was business as usual…

The DEC4 Podcast will be back with our end-of-year special, once again featuring Gary Wells. Thanks to everyone who reads, listens, and shares us on social media. Get in touch here, on Tumblr, Facebook, Instagram, or at the DEC4 Webpage, where you can also link to our social media.

Special Thanks to Steve Collins, Gainesville, and the Armstrong and Burton book series for sponsorship, technical and creative support.

That's a good in-depth look at Elvis' world at the point where it came to an end. The only problem that stood out was the reference to the Mexican Sundial jumpsuit, where the caption said "There were apparently two identical versions of this suit." I think that myth started with the Jerry Hopkins book ''Elvis: The Final Years'' which incorrectly stated that there were two identical suits. While talking about the CBS TV special, the book stated that Elvis alternated between them as he wore one while the other was being cleaned. Understandably, that detail got passed on by readers to the point that it it was believed by many fans, even some who consider themselves 'jumpsuit junkies.' It turns out that it was incorrect. Gene Doucette, the tailor responsible for the styling of all of Elvis' wardrobe (both onstage and streetwear) was quite explicit about only ever having made one such jumpsuit in a YouTube video. As well as the Mayan Calendar design, he incorporated the art deco shape of the top of New York's Chrysler Building into the embroidery on either side of the bell bottom kick pleats.

In every other respect, this article is a great summary in your broader look at each phase of his life.