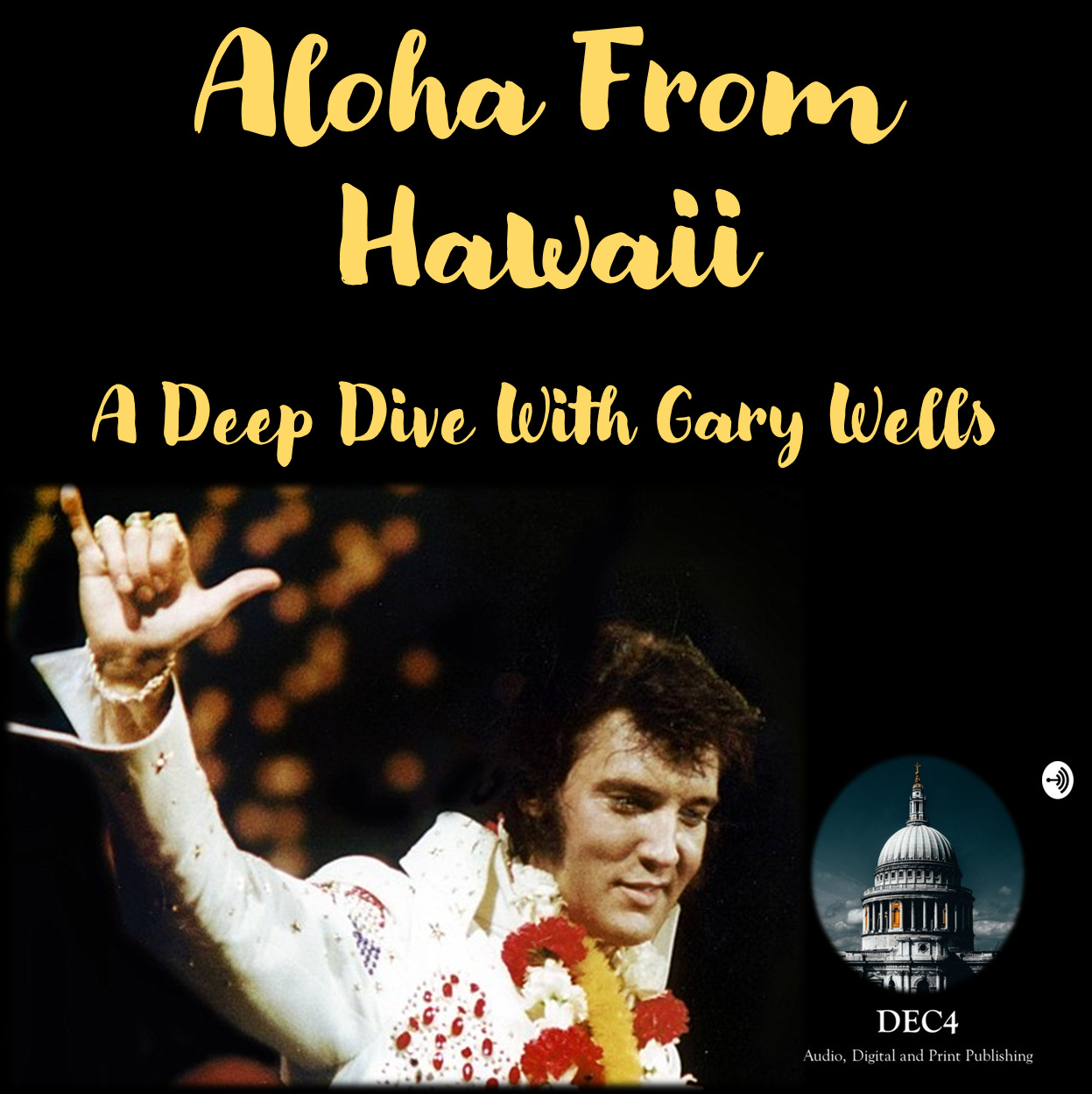

DEC4 Podcast Companion: Elvis Aloha From Hawaii - Episode 3 with Gary Wells

The repackaged TV special, the live album, and what happened next...

In this companion newsletter to our final of three DEC4 Podcast episodes taking a deep dive into Elvis Aloha From Hawaii, Gary Wells (soulrideblog.com) joins us once again as we discuss the post-concert album and single releases, as well as the expanded version of the show that aired on NBC in the US nearly three months after the live event. It was a ratings smash all over again, and became NBC’s most watched programme for the year.

Before we move on, a BIG thank you to Adam, who got in touch since the last episode, to raise the issue of the iconic ticketing style, and generously shared some additional background information with us.

Interesting that it gives showtime as 1.00 am when every other source, including Wayne Harada in Honolulu Advertiser, says 12.30 am curtain.

There is a little more background here, at the website of Robert Edwards Auctions, when the above tickets were sold for $ 2700 in 2016.

Soon after the satellite show, Elvis was already back at work in Las Vegas as the live album came out, and went to #1 (Billboard). Steamroller Blues was subsequently released as the single, climbing to #17 on Billboard and #10 on Cashbox.

With Elvis’ personal producer, Felton Jarvis, convalescing from his kidney transplant, the album project was helmed by Joan Deary, the first female senior executive in RCA Records’ history. It appears that she felt that Elvis’ crew was a little out of their depth in terms of the latest technology, with the Aloha album to be released in Quadrophonic. She wasn’t a fan of the setup at Stax either, where upcoming sessions were to take place, and her attitude seemed to reflect a feeling within RCA that a greater degree of supervision needed to be applied to Elvis’ studio work.

On April 4th, 1973, NBC aired the expanded version domestically in the US, complete with Hawaiian scenery footage and the insert tracks that had been recorded directly after the show. The live performance aspect remains a stunning piece of television even half a century on, not only due to Elvis’ undoubted talents but to the ability of Marty Pasetta to showcase a star, on screen, in the most favourable and polished way imaginable. As the concert footage has been reedited from scratch for DVD releases, this is the only way we can see Marty Pasetta’s pure vision for the special, and exactly how audiences saw it half a century ago.

The programme, as we’ve said, rated through the roof, and was generally well received critically, although perhaps with not quite the same enthusiasm as the satellite broadcast. Writer and critic Dave Marsh opined that it diminished Elvis’ on stage energy, overused the multi-screen montages, the time between the live event and the special lessened the impact, and that Elvis appeared ‘weirdly distanced’ from his audience.

It was in the context of this stunning and unprecedented commercial and artistic success that RCA Records moved to gain greater control over the untapped goldmine of Elvis’ back catalogue, keen to free themselves from Colonel Parker’s constant meddling. RCA made an offer to Parker of 3 million dollars to secure sole rights, an amount which through negotiation rose to 5.4 million. Although it would mean a cash windfall for both Elvis and the Colonel, they would no longer benefit from the ongoing income from record sales encompassing Elvis’ biggest hits. They would, from then on, need to rely on revenues from dwindling sales of new material, over and above their contract guarantees, Vegas engagements and the ever-lucrative touring circuit.

Credible sources suggest that Elvis was right behind this deal, and this perhaps represents one of the finale periods of genuine unity between Elvis and his manager and, in fact, in the early hours of January 14th following the satellite broadcast, Colonel had written Elvis a heartfelt letter of appreciation, ‘You above all make it all work by being the leader and the talent. Without your dedication to your following, it couldn’t have been done’.

By the time a number of side deals were ratified, including merchandising revenues, supply of promotional material to support record releases, guarantees against future royalties under a new seven year contract, bonuses and other complicated arrangements probably not understood by anyone other than Parker himself, Elvis’ share of the entire mess would be 4.5 million dollars to Colonel Parker’s 6 million, according to Peter Guralnick’s analysis in his biography, Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley. Tour revenues would be accounted differently, with projected earnings of 15 million dollars, of which Elvis would keep 10 million. This apparently, in a roundabout way, all eventually added up to the famously controversial 50/50 arrangement between Elvis and his manager. But there were some unintended consequences, with Parker forced to intervene to prevent greatest hits souvenir compilations, curated by Joan Deary, being released in direct competition with Elvis’ new material. RCA had to concede, promising better communication and consultation with Parker’s office in relation to the timing of catalogue releases. They never did quite get rid of him after all.

The Aloha event, in all its forms, was really the final time Elvis dominated the world stage, attracted saturation media coverage, and reached the top of the charts, in his own lifetime at least, and the scene was now set for the remainder of Elvis’ career. His expensive lifestyle and large business operation needed to be supported, and the only way to bring in big money consistently was on tour, a relentless treadmill that made no allowance for exhaustion or ill health. The general narrative of Elvis’ remaining short life and career has certainly been generalised in terms of ‘decline and fall’, although is this really fair? He battled ill-health, weight and addiction, and there were some off nights on the road, but he was still filling big arenas and putting on great shows right to the end, his final concert in Indianapolis a case in point. Contrary to myth, this was not filmed officially but does, however, exist by virtue of a bootleg audience recording, as linked here (audio only).

At the time of his death, on the eve of a road tour which was to conclude with two shows at the Mid-South Coliseum, Memphis, he was also booked to headline the opening of the Hilton Pavilion, a 5 000 seat showroom which was part of a major redevelopment of the Las Vegas Hilton.

In the absence of official vision and sound covering the period between Aloha and Elvis’ final tour, many biographers have relied on the press reviews of later concerts to form their opinions, in the days before YouTube and other platforms gave us the chance to make up our own minds. In a recent Substack piece, we explored a specific instance of how press reaction and reality diverged dramatically, yet the press version had been relied upon as true record. The example taken is St Paul, Minnesota, in 1977, when it seems that, in the cause of a hatchet piece, almost total uncritical credence was placed on a source of questionable reliability.

But to round off our series; the entire Aloha From Hawaii project was a remarkable achievement by a once-in-a-century collection of people with talent, vision and courage, led by a uniquely gifted artist. Did any other entertainer have the universal following that transcended multiple generations, or the ability and showmanship to pull something like this off, at that time? As Gary said at the end of episode two of our podcasts, “Only Presley.”

We really do hope that you’ve enjoyed sharing this Aloha From Hawaii adventure with us.

Some suggestions for further reference;

Gary Wells’ website has some great Elvis background, including a fascinating piece on Memphis attorney Blanchard E Tual and his attempts to unravel the complexities of Colonel Parker’s business dealings on behalf of the Presley estate.

https://soulrideblog.com/category/elvis-presley/

https://soulrideblog.com/2019/01/06/elvis-week-2019-blanchard-e-tual-hero/

Elvis in Hawaii is an older website well worth checking out for background facts and some rare behind-the-scenes images.

http://www.elvisinhawaii.com/aloha-menu.html

Elvis Presley In Concert, a website and database by Francesc Lopez, is a definitive reference for concert stats, schedules, reviews, live CD releases and jumpsuit information.

https://www.elvisconcerts.com/

A YouTube playlist of Elvis concerts and key moments, some recorded at the soundboard, others by audience members and later bootlegged, from 1974-77. There are also extracts from press reviews, concert stats and tour facts, and many comments from people who were actually at the shows and who give a great personal insight into the Elvis experience.

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLyLCvjIW2RVQOXSr3kqz3kYcsULaLAvre